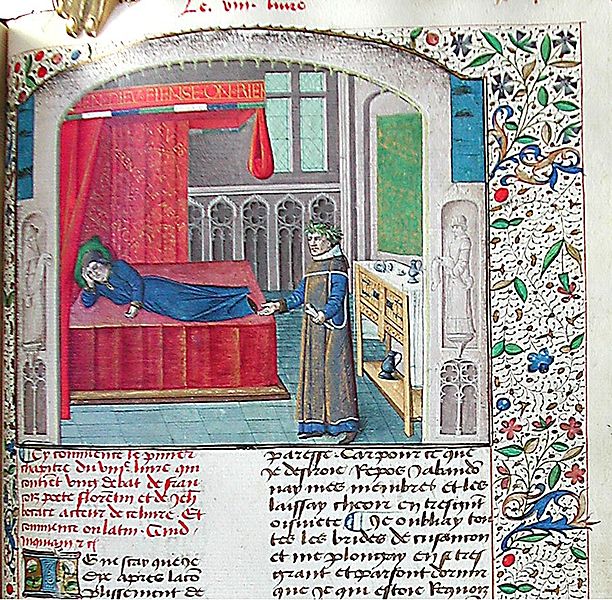

De Casibus Tragedy

My favorite definition:(call it the de casibus model, meaning 'of the falls of kings and princes') Tragedy is to seyn a certyn storie, As olde bookes maken us memorie, Of hym that stood in greet prosperitee, And is yfallen out of heigh degree Into myserie, and endeth wrecchedly. And they been versified communely. In tragedy: The long hiatus of life, and the word tragedy again came into currency. Geoffrey Chaucer used the word in Troilus and Criseyde, and in The Canterbury Tales it is applied to a series of stories in the medieval style of de casibus virorum illustrium, meaning “the downfalls (more or less inevitable) of princes.”. De Casibus Virorum Illustrium On the Fates of Famous Men is a work of 56 biographies in Latin prose composed by the Florentine poet Giovanni Boccaccio of Certaldo in the form of moral stories of the falls of famous people, similar to his work of biographies De Mulieribus Claris. The play has been called “an almost perfect example of de casibus tragedy in its formal structure and in its technical mastery.” 2 The pattern of rise and fall evokes the traditional. Tragedy - Tragedy - The long hiatus: The Roman world failed to revive tragedy. Seneca (4 bce–65 ce) wrote at least eight tragedies, mostly adaptations of Greek materials, such as the stories of Oedipus, Hippolytus, and Agamemnon, but with little of the Greek tragic feeling for character and theme. The emphasis is on sensation and rhetoric, tending toward melodrama and bombast.

Table of Contents

I INTRODUCTION

A Time and Authorship

В The play

1. General Remarks

2. Content

a A Virtuous King

b Three Evil Actions Initiating Cambises’ Fall From Virtue

c Two More Evil Actions Leading to Cambises’ Death

C Shakespeare and Cambises

II MAIN PART

A A Hybrid Play

1. A Morality Play

a Definition

b Elements of the Morality Play in Cambises

i Ambidexter !

ii Morality Abstractions

in Symbols of Sin พ

c Intention

2. A History Play IO

a Definition״

b Elements of the History Play in Cambises

i Cambyses

ii Mary

iii Henry VIII

c Intention

3. A (De Casibus) Tragedy

a Definition

b Elements of the (De Casibus) Tragedy in Cambises

c Intention.״

4. Farce/Comedy

a Definition״

b Elements of the Farce/Comedy in Cambises

i Ambidexter’s role

ii Comic interludes

c Intention

В Orientalism in Cambises

1. Edward Said’s “Orientalism”

2. Orientalism on stage

3. Intention

III CONCLUSION

A Summary

В Open Questions

IV WORKS CITED

I Introduction

In this paper, I am going to show that the play Cambises by Thomas Preston is a very complex play combining different kinds of traditions, namely the morality play, the history play, the (de casibus) tragedy, and the comedy or farce.

After some general remarks concerning the time the play was written, its author, the content of the play and Shakespeare’s knowledge of the play, I am going to explain in detail how each of these traditions comes into play by showing in how far the play matches the definitions of each tradition. This will be followed, in each instance, by a hypothesis about the different traditions’ intentions. I will, then, briefly look at the influence of Orientalism on the play. The conclusion will, first of all, sum up this paper, and, afterwards, address some open questions that could not be addressed in this paper but would still be interesting to look at in order to get a better understanding of the play.

A Time and Authorship

Cambises was written around 1560 and probably published, with several press variants[1], in 1569. According to Johnson[2], the first performance of the play may have taken place at court during Christmas 1560/1561.

The author of the play is a man called Thomas Preston. Critics are still debating about whether or not this Thomas Preston was the same man who was a Master of Trinity College and the Vice-Chancellor of the university, or just someone who happened to bear the same name.

The critics who object to the idea of Thomas Preston, Master of Trinity College, as the author argue that this name was a fairly common name at the time. Moreover, they charge the author of dramatic ineptitude due to the play’s pretty bad style so that, for them, it is impossible that an acclaimed scholar may have written it.

Those critics who believe that the Vice-Chancellor of the university is the author of the play, after all, do so because the play, despite its bad style, still shows a great complexity. They say that the play was originally written for political ends and that parts of the play have probably been added later in order to adapt the play to a popular audience and to the touring conditions of the small company of players common at the time.[3]

В The play

1. General Remarks

As the list of players reveals, the play is designed for eight actors. According to Johnson, most probably, the group consisted of six men and two boys[4]. It was common, in the 16th century, that even women’s roles were played by male actors, and that the company of players included one or two boy actors. The play is not divided into acts or scenes, however, Johnson says that there are eleven definite parts[5].

Several critics, among others Johnson and Wentersdorf, share the opinion that the play is based on Richard Taverner’s Garden of Wysedome since there is a striking resemblance between the outline and some of the details to be found in both the Garden of Wysedome and Cambises. Moreover, the same incidents appear in the same order and both works can be considered part of the Mirror for Magistrates tradition. Preston combined this source with the factual life of Cambyses, king of Persia.

Even thought the play is entitled Cambises, I share Johnson’s opinion that there are actually two protagonists and two different intentions behind the play. Due to the intermingling of comical interludes and rather serious episodes, the serious part of the play can be considered a study of tyranny with Cambises as its hero. This is the part that, according to the critics referred to above who believe that Thomas Preston, Master of Trinity College, is the author of the play, was actually written by Thomas Preston. The parts they believe to have been added later, i.e. mainly the comical interludes and the vice Ambidexter, make a study of ambidexterity of the play as a whole with Ambidexter at the center.[6]

2. Content

Basically, Cambises traces the degeneration of King Cambises of Persia,[7]

a A Virtuous King

In the first part of the play, Cambises starts off as a man of virtuous upbringing who takes off to conquer Egypt. He appoints the judge Sisamnes governor so he can take Cambises’ place for the time he cannot rule himself. Ambidexter, a vice figure, lures Sisamnes into abusing of his power.

b Three Evil Actions Initiating Cambises’ Fall From Virtue

The second part of the play covers the first three of five evil actions leading to the downfall of king Cambises.

Upon his return, he learns about Sisamnes’ abuse and orders his execution. I consider this execution of a corrupt judge, which is called a good deed in the introduction of the play, the first evil deed initiating Cambises’ fall from virtue into sin.

After Sisamnes’ execution, Praxaspes, a man very close to Cambises, admonishes Cambises not to drink as much alcohol as he actually does. In order to prove is sobriety, Cambises kills Praxaspes’ son and has a lord and a knight cut out the child’s heart. This killing of an innocent child is, for me, the second evil action of Cambises.

In what follows, Ambidexter tries to make Smirdis, Cambises’ brother, jealous of the king and, immediately after having been turned down by Smirdis, he tells the king his brother wants him dead so he can be king himself. This leads to the execution of Smirdis by figures called Crueltie and Murder. The execution of his innocent brother is, in my opinion, the third evil action Cambises commits.

c Two More Evil Actions Leading to Cambises’ Death

The third part of the play contains the last two evil actions leading, in the end, to Cambises’ death.

Cambises falls in love with his cousin and forces her into marriage. This can be considered the fourth evil action because incest is nothing virtuous really even if it is less cruel than killing people.

The division into parts and scenes is taken from Johnson (1975)

However, when the queen mourns Smirdis’ death Cambises orders her execution, as well, which concludes the series of evil actions. In one of the last scenes Cambises dies from an injury and says that this was the just reward for all his evil deeds.

C Shakespeare and Cambises

Many critics of Elizabethan theatre, among them Johnson, suggest that Shakespeare must have known Preston’s Cambises when writing his plays Henry IV and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, among others.

The following passage is taken from Henry IV

illustration not visible in this excerpt

Henry rv, II.iv.421-437[8]

If we compare this passage to the scene in Cambises where the death of the queen is ordered we can see that there is a great resemblance between the two scenes.

illustration not visible in this excerpt

Cambises 1041 ff.

Another parallel to Shakespeare’s works can be found in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. There is a group performing a play that satirically seems to allude to Cambises when Quince describes their play as

“The most lamentable comedy and most cruel death of Pyramus and Thisby”[9]

So after looking at these two passages, it seems to be clear that Shakespeare actually knew Preston’s play.

II Main Part

Now I want to turn to the actual topic of this paper, the hybrid nature of Cambises.

A A Hybrid Play

According to critics, Cambises ...

... deals “with quasi-historical material in a way typical of the morality play”[10]

... is a “prime example of the hybrid-morality play”[11]

... is the “earliest surviving tragedy of the Elizabethan age”[12]

and, as the subtitle of the play suggests, it is

“a lamentable tragedy mixed ful of pleasant mirth, conveying the life of Cambises king of Percią, from the beginning of his kingdome unto his death, his one good deed of execution, after that many wicked deeds and tyrannous murders, committed by and through him, and last of all, his odious death by Gods Justice appointed”[13]

This makes clear that Cambises cannot be assigned to one single category of drama. The play was written in a transitional period of the English popular stage. According to Hill,

IV Works Cited

[Anonymous] : The Bible. 08.08.2004. http : //www.bible. com

[Anonymous] : Notes on Tragedy and Comedy. 30.06.2004.

http://www.gradlittersnotes.com/tragedvnotes.htm.

[Anonymous]: SDTV: Shakespeare Transcript. 30.06.2004.

http://www.pbs.org/standarddeviantstv/transcript shakespeare.html.

[Anonymous]: Tragic Mirth: King Comby ses. 30.06.2004.

http://ise.uvic.ca/Librarv/SLTnoframes/drama/cambvses.

[Anonymous]: “Thomas Preston,” in: Walter Jens (ed.): Kindlers neues LiteraturLexikon. Vol. 13. Munich : Kindler 1991.

Ashcroft Billand Pal Ahluwalia: Edward Said. London : Routledge 2001.

Bellinger, Martha: The Chronicle and History Play. 30.06.2004.

http://www.theatrehistorv.com/british/bellingeroo2.html.

Blue, Tina: The morality play in English drama. 30.06.2004.

http : / /riri · essortment.com/englishdrama ri dz .htm .

Gudemann, Wolf-Eckhard (ed.): Bertelsmann Universal Lexikon. Vol. 20. Guetersloh: Bertelsmann Lexikothek 1990.

Happé, p.: “Tragic Themes in Three Tudor Moralities,” in: SEL: Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900. 5 (2). 1965 Spring. 207-227.

Heywood, Thomas and John Green : An Apology for Actors. New York, NY : Garland

1973·

Hill, Eugene D.: “The First Elizabethan Tragedy. A Contextual Reading of Cambises,” in: Studies in Philology. 89 (4). 1992 Fall. 404-433

Johnson, Robert Carl: “Thomas Preston’s Cambises,” in: Dissertation Abstracts. 25. Ann Arbor, MI: 1965. 4688.

Johnson, Robert Carl: a critical edition of Thomas Preston’s Cambises. Salzburg: University of Salzburg 1975.

Mackenzie, John: Orientalism: history, theory, and the arts. Manchester : Manchester Univ. Press 1998.

Norland, Howard B.: “‘Lamentable tragedy mixed ful of pleasant mirth’: The Enigma of Cambises,” in: Comparative Drama. 26 (4). 1992-1993 Winter. 330-343.

Shakespeare, William: The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth 1996.

Taylor, Anthony Brian: “The Clown Episode in Titus Andronicus, the Bible, and Cambises,” in: Notes and Queries. 46 (244) (2). 1999 June. 210-211.

Wentersdorf, Karl p.: “The Allegorical Role of the Vice in Preston’s Cambises,” in: Modern Language Studies. 11 (2). 1981 Spring. 54-69.

[...]

[1] The press variants can be found, for instance, in JOHNSON, Robert CARL: A critical edition of Thomas Preston’s Cambises. Salzburg: University of Salzburg 1975.

[2] Johnson 1975: 29

[3] A further exploration of the question of authorship can be found in Norland, Howard B.: ‘“Lamentable tragedy mixed ful of pleasant mirth’: The Enigma of Cambises,” in: Comparative Drama. 26 (4). 1992-1993 winter. 330-343.

[4] Johnson 1975:151

[5] Johnson 1975:161

[6] Johnson 1975: 22

[7] The division into parts and scenes is taken from Johnson (1975)

[8] Quoted from Johnson 1975: 33

[9] Shakespeare 1996, 282

[10] Happé 1965: 207

De Casibus Tragedy Definition

[11] Johnson 1965: 4688

[12] Hill 1992: 407

De Casibus Tragedy Definition

[13] Johnson 1975: 45